This tutorial discusses how you can easily write your own Bash scripts on Linux.

As a system administrator, it is quite likely that you are performing repetitive tasks that could be automated.

Luckily for you, there is a programming language that can be used on Linux in order to write scripts : the Bash programming language.

Using Bash, you can schedule entire system backups by specifying as many commands as you want in Bash scripts.

You can also have custom scripts that create and delete users and remove their associated files.

With Bash, you can also have scripts running and dumping useful performance metrics to a file or database.

Bash is a very powerful programming language for system administrators.

In today’s tutorial, we are going to learn all the basics that there is to know about Bash : how to create and run scripts, how to use variables and shell built-ins effectively.

What You Will Learn

If you read this tutorial until the end, you are going to learn about the following concepts regarding Bash

- How to create and run Bash scripts using the command line;

- What shebang is and how it is used by Linux for scripting;

- What shell built-ins are and how they differ from regular system programs;

- How to use Bash variables and what special variables are;

- How to use Bash command substitution;

- How to use simple IF statements on Bash;

As you can see, this is quite a long program, so without further ado, let’s start by seeing how you can create and run Bash scripts.

Getting Started with Bash

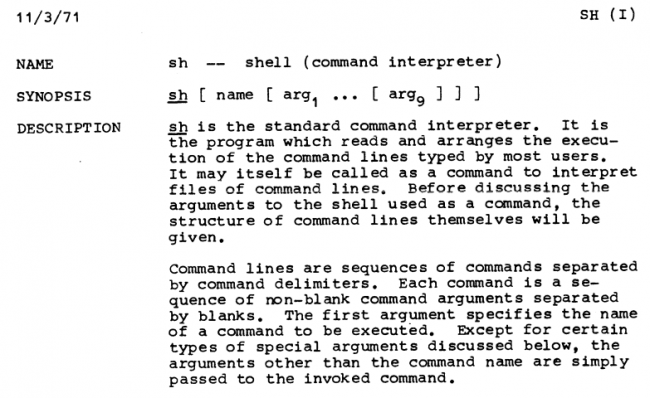

Before issuing any commands, let’s have a quick word on Bash and Shell common histories.

History of Bash

The first version of the Bash shell was released in 1989 by Brian Fox and it comes as an open-source implementation of the Unix shell.

Back then, as Unix systems started to arise, such systems were using standard Unix shells named Bourne shells.

In the early days of Unix, systems developed by companies such as the MIT or Bell Labs were not free and they were not open-source.

Even if documentation was provided for those tools, it became a priority for the GNU initiative (led by Richard Stallman) to have its own version of the Unix Shell.

Six years after announcing the GNU project, the Bash (Bourne-Again Shell) shell was born with even more features than the original Bourne shell.

Bash programming language

When working with a Unix-like system such as Linux, Bash usually has two meanings :

- Bash is a command-line interpreter or in other words a Unix shell. It means that whenever you are opening a terminal, you will be facing a Unix shell that is most of the time a Bash shell.

When typing commands directly in the terminal, commands are interpreted by the shell, executed using system calls and return values are given back to the end-user.

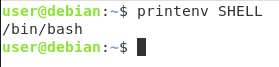

If you are not sure about the current interpreter that you are using, the SHELL environment variable indicates which shell you are currently using.

$ printenv SHELL

As you can see, in this case, we are correctly using the Bash command interpreter to work.

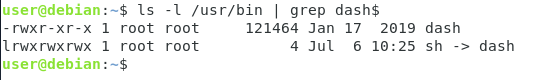

It is important to note that even if terms like “Bash scripting” and “Shell scripting” are used interchangeably, they might not actually describe the same thing depending on your distribution.

Some recent distributions (such as Debian 10) have symbolic links from the original Bourne shell (named sh) to their own shell implementations (in this case Dash or Debian Almquist shell)

- Bash is also describing a command-line language and it is also referred as the Bash language. Bash exposes a set of operators and operands that can be used in order to have some basic features such as piping or executing multiple commands at once.

When executing some basic piping, you are used to work with the “|” symbol. This symbol is part of the Bash command-line language.

The same logic goes for the “&&” symbol that executes the second command if, and only if, the first command succeeded.

$ command1 && command2

Create and Run Bash Scripts

Now that you have some background about the Bash shell and the Bash command-line language, let’s start by creating and running simple Bash scripts.

In order to create your first Bash script, simply create a file named “script.sh”.

As you probably already noticed, we are still using the “sh” extension referring to the original Bourne shell (also denoted as sh).

$ touch script.sh

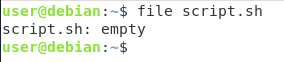

Now creating a file ending with the “sh” extension is not enough for your script to be considered as a Shell script.

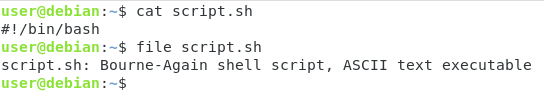

You can actually see that your file is not yet considered as a shell script by running the file command.

$ file script.sh

As you can see here, your file is only described a simple empty file.

In order for your file to be described as a shell script file, you need to specify the shebang line at the top of your file.

Specifying shell using shebang

If you have been using Linux for quite some time, it is very likely that you have already encountered the shebang line at the beginning of your file.

Shebang, short for “Hash + “Bang”, is a one-liner set at the beginning of shell scripts in order to specify which shell is to be used to interpret this script.

#!/bin/<shell>

In our case, we want to work with Bash scripts. In other words, we want our scripts to be interpreted by a Bash interpreter.

In order to determine the path to the interpreter, you can use the “which” command.

$ which bash /bin/bash

Now that you know the path to your interpreter, edit your script file and add the shebang line at the top of your file.

#!/bin/bash

Now that you have added this line at the beginning of your file, re-execute the “file” command in order to see the difference.

As you can see, the output is slightly different : this time, your script is seen as a “Bourne-Again shell script” and more importantly as an executable.

So what would happen if you didn’t specify the shebang line at the top of the script.

When not specifying the shebang line, the script is run using the current shell used in order to start the execute command.

Now that you know how to create Bash scripts, let’s see how you can executing them.

Execute Bash Scripts

In order to execute Bash scripts on Linux, you essentially have two options :

- By specifying the shell interpreter that you want to use and the script file;

- By using the path to the script file

Specifying the shell interpreter

The first method is pretty straightforward.

In order to execute your bash script, you are going to specify the interpreter that you want to use by yourself.

$ bash <script> $ /bin/bash <script>

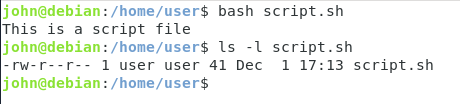

Using the example that we used before, this would give us the following output.

As you can see, this method does not even require the execute permissions on the file, you just need to be able to use the bash executable.

As you can see, when logged as another user, without execute permissions, I am still able to execute this script.

This is an important remark because you might want to store your script files in protected directories (that only you can access) in order to prevent other users from executing your files.

Specifying the path to the script

The other way to execute bash scripts is to specify the path to the file.

In order to use this method, the file needs to have execute permissions.

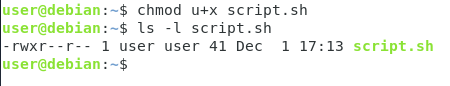

First, use the “chmod” command in order to set execute permissions for the current user.

$ chmod u+x <script>

As you can see, the file color is quite different : your current terminal highlights executable files using specific colors, in this case the green color.

Now that your script is executable, you can execute it by specifying the relative or absolute path to the script.

Using a file named “script.sh” located in my current working directory, the script can be executed by running

$ ./script.sh

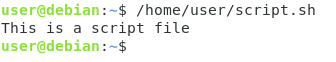

If you are in another directory, you will have to specify the absolute path to the script file.

$ /home/user/script.sh

As you probably realized by now, this method is not very convenient if you have to specify the path to the script every single time.

Luckily for you, there is a way to execute your script by simply typing the filename in the command-line.

Adding the script to PATH

The “.sh” extension is not needed for a script to be considered a script file.

For the sake of simplicity, we are going to rename the existing “script.sh” file to “script”.

To rename files on Linux, simply use the “mv” command and specify the source and destination targets.

$ mv script.sh script

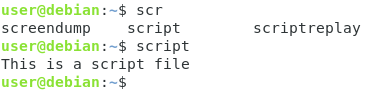

Now, what if you wanted to execute your script by typing “script”?

In order to do that, you have to add the path to your script to your PATH environment variable.

To print the current value of your PATH environment variable, use “printenv” with the “PATH” argument.

$ printenv PATH

To update the PATH in your current working environment, edit the PATH environment variable using the following syntax.

$ export PATH="<path_to_script>:$PATH"

Now, the “script” command you just defined will be directly available without specifying any paths : you can launch it like any other commands.

Note : if you want to make your changes permanent, follow those steps to update your PATH variable properly.

Shell built-ins explained

Before declaring any variables in your shell script, it is important for you to know about shell built-ins.

When you are working with the Bash shell, you are most of the time executing “programs“.

Examples of programs are “ls”, “fdisk” or “mkdir”. Help for those commands can be found by using the “man” command short for “manual”.

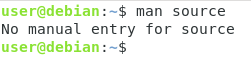

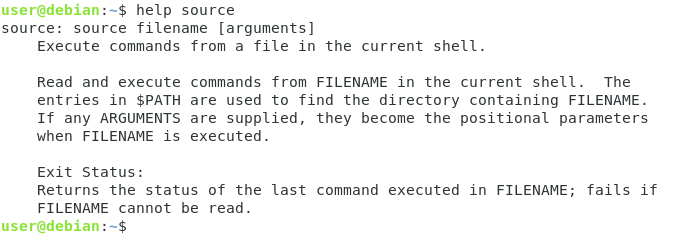

However, have you ever tried to read the documentation for the “source” command?

You would not be able to read the documentation using “man” because the source command is a shell built-in function.

In order to read the documentation for shell built-ins, you have to use the “help” command.

$ help <command>

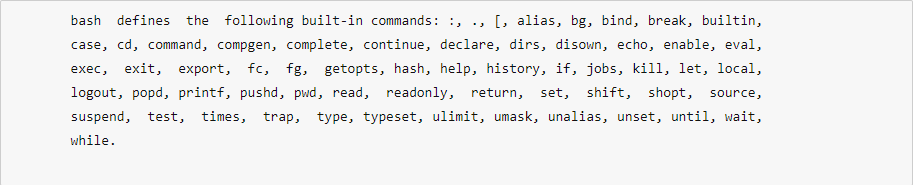

The list of shell built-ins is quite extensive but here is a screenshot of every bash built-in command that you may find on Ubuntu systems.

Using Bash Variables

Now that you know about Bash built-ins, it is time for you to start writing your own Bash scripts.

As a reminder, the commands typed in your terminal can be used in a Bash script in the exact same way.

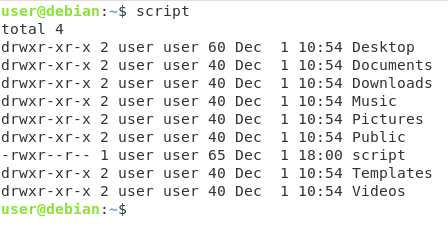

For example, if you want a script that simply executes the “ls -l” command, simply edit your script, add the shebang line and the command.

#!/bin/bash # This simple script executes the ls command ls -l

Now, what if you wanted to have Bash variables?

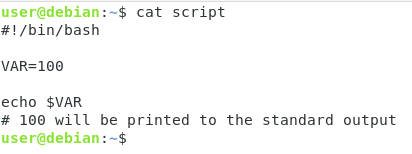

Bash variables are simple program variables that can store a wide variety of different inputs.

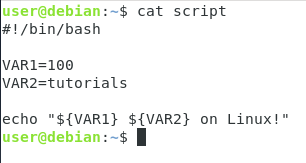

To declare a Bash variable, simply specify the name of the variable and its value separated by an equal sign.

VAR=value

In order to be able to use the content of your Bash variable in your script, use “$” and append the name of your variable.

echo $VAR

Even if you can use this syntax in order to have the variable value, you can also use the “brackets” notation.

echo ${VAR}

Using this syntax, variables can be combined together.

If you have two Bash variables named VAR1 and VAR2 for example, you can have them both printed using the following syntax

echo "${VAR1}${VAR2}"

Executing commands within scripts

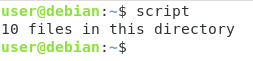

In order to execute commands inside Bash scripts, you have to use command substitution.

Command substitution is a technique used in Bash shells in order to store the result of a command in a variable.

To substitute a command in Bash, use the dollar sign and enclose your command in brackets.

VAR=$(command)

For example, in order to get the result of the numbers of files in your current directory, you would write

#!/bin/bash

NUMBER=$(ls -l | wc -l)

echo "${NUMBER} files in this directory!"

As you can see, command substitution is pretty handy because it can be used to dynamically execute commands in a shell script and return the value back to the user.

Speaking about returning results to the end-user, how do you handle scripts not terminated correctly?

What if a command inside the script did not execute properly?

Understanding Exit Statuses

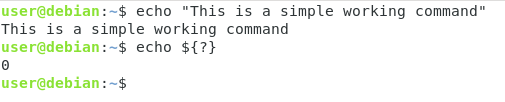

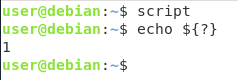

When you are executing a script, even if you are not returning a value, the script always returns what we call “an exit status”.

An exit status in Bash scripting indicates whether the script execution was successful or not.

If the status code is zero, your script execution was successful. However, if the value is any different from zero (say one, two or more), it indicates that the script execution was not successful.

To demonstrate the exit status, run any valid command in your bash shell.

echo "This is a simple working command"

Now, use this command in order to inspect the exit status of the last command run.

echo ${?}

As you can see, the output of this command is “0” or the exit status of the last command I executed.

This syntax (“${?}”) can be used in scripts in order to make sure that commands executed properly.

The exit status can be used in scripts in order to exit the script with a specific status code.

For example, if you want to exit the script with an error, you can use the following command in your script.

exit 1

Similarly, you can use the “zero” exit code in order to specify that the script executed successfully.

exit 0

In order to verify if the status code was correct, you are going to need basic conditional statements such as the IF statement.

Manipulating conditions in Bash

Sometimes, executing bash scripts is not only about having multiple commands next to each other : you want to have conditional actions.

In some cases, it might be handy to have a condition checking whether the current user is the root user (or just a specific user on your system).

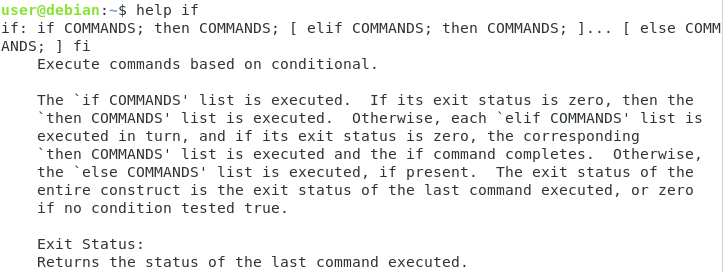

One simple way to have conditions in Bash is to use the if statement.

“If” is shell built-in, as a consequence, the manual is available via the “help” command

$ help if

The help page describes the syntax for the if command using semi-colons, but we are going to use this syntax (that is equivalent)

if [[ condition ]] then <commands> else <command> fi

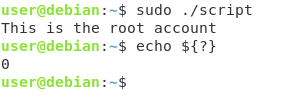

Practice case : checking if the user is root

In order to showcase what the if statement can be used for, we are going to write a simple script checking whether a user if the root user or not.

As a reminder, the root user always has the UID set to zero on any Unix system.

Knowing this information, we are going to check whether the UID is set to zero, if this is the case, we are going to execute the rest of the script, otherwise we are going to exit the script.

As explained in other tutorials (about user administration), you can get the current user ID by using the “id” command.

$ id -u 1000

We are going to use this command in order to check whether the user executing the script is root or not.

Create a new script and add the shebang line to it.

#!/bin/bash

Right below it, add the “id” command and store the result in a variable named “USERID” using command substitution.

USERID=$(id -u)

Now that the “USERID” contains the current user ID, use an IF statement in order to check whether the user ID is zero or not.

If this is the case, write a simple informational message, if not exit the script with an exit status of 1.

if [[ "${USERID}" -eq 0 ]]

then

echo "This is root"

else

exit 1

fi

Now if you execute the script as your current user, the script will simply exit with an exit status of one.

Now, try to execute the script as the root user (with the sudo command)

As you can see, your informational message was displayed and the script exited with an error code of zero.

Conclusion

In this tutorial, you learnt about the Bash programming language and how it can be used in order to create Bash scripts on your system.

You also learnt about exit statuses and conditional statements that are key in order to have custom logic set into your scripts.

Now that you have more knowledge about Bash, you should start by writing your own scripts for your needs : you can start by having a tutorial on create archive backup files for example.

If you are interested in Linux System administration, we have a complete section dedicated to it on the website, so make sure to check it out!