As a Linux system administrator, inspecting log files is one of the most common tasks that you may have to perform.

Linux logs are crucial : they store important information about some errors that may happen on your system.

They might also store information about who’s trying to access your system, what a specific service is doing, or about a system crash that happened earlier.

As a consequence, knowing how to locate, manipulate and parse log files is definitely a skill that you have to master.

In this tutorial, we are going to unveil everything that there is to know about Linux logging.

You will be presented with the way logging is architectured on Linux systems and how different virtual devices and processes interact together to log entries.

We are going to dig deeper into the Syslog protocol and how it transitioned from syslogd (on old systems) to journalctl powered by systemd on recent systems.

Linux Logging Types

When dealing with Linux logging, there are a few basics that you need to understand before typing any commands in the terminal.

On Linux, you have two types of logging mechanisms :

- Kernel logging: related to errors, warning or information entries that your kernel may write;

- User logging: linked to the user space, those log entries are related to processes or services that may run on the host machine.

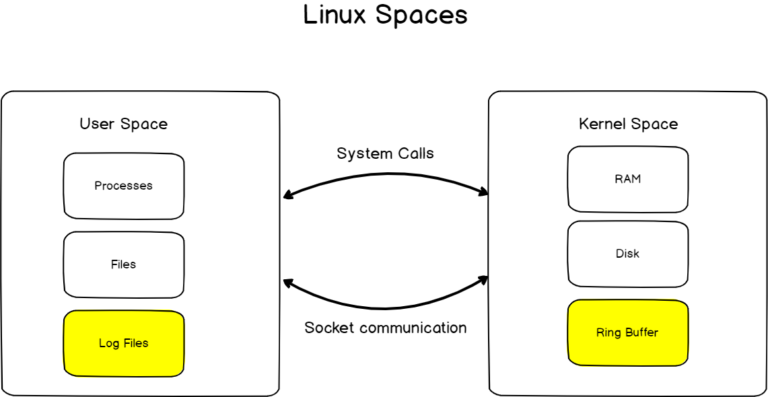

By splitting logging into two categories, we are essentially unveiling that memory itself is divided into two categories on Linux : user space and kernel space.

Kernel Logging

Let’s start first with logging associated with the kernel space also known as the Kernel logging.

On the kernel space, logging is done via the Kernel Ring Buffer.

- Syslog: The Complete System Administrator Guide

- The Definitive Guide to Centralized Logging with Syslog on Linux

- Docker Logs Complete Guide | Definition of Docker Logs, Logging Strategies & Best Practices

The kernel ring buffer is a circular buffer that is the first datastructure storing log messages when the system boots up.

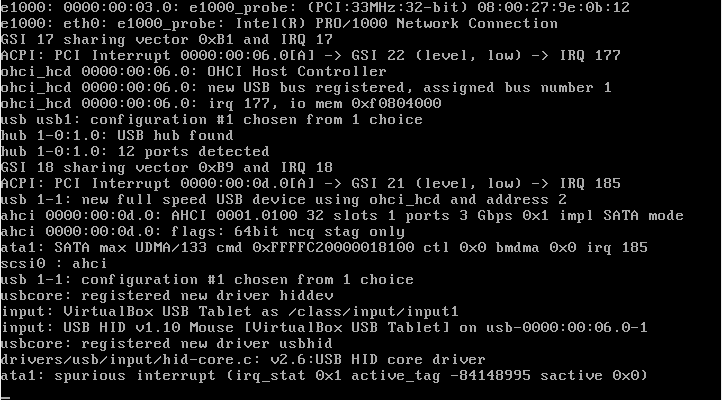

When you are starting your Linux machine, if log messages are displayed on the screen, those messages are stored in the kernel ring buffer.

The Kernel logging is started before user logging (managed by the syslog daemon or by rsyslog on recent distributions).

The kernel ring buffer, pretty much like any other log files on your system can be inspected.

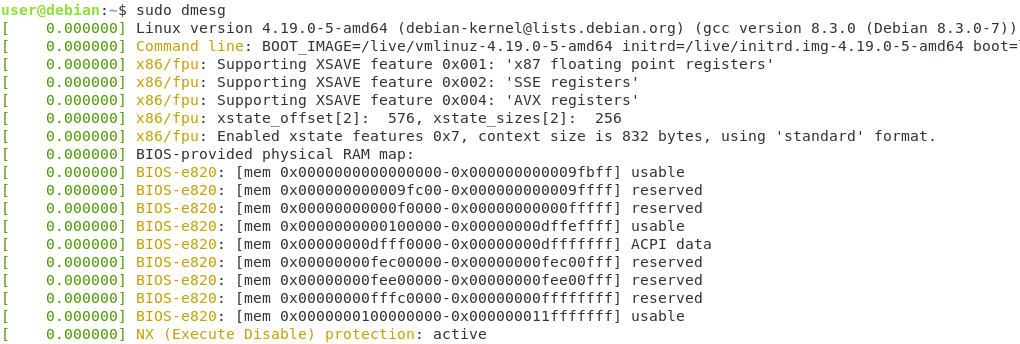

In order to open Kernel-related logs on your system, you have to use the “dmesg” command.

Note : you need to execute this command as root or to have privileged rights in order to inspect the kernel ring buffer.

$ dmesg

As you can see, from the system boot until the time when you executed the command, the kernel keeps track of all the actions, warnings or errors that may happen in the kernel space.

If your system has trouble detecting or mounting a disk, this is probably where you want to inspect the errors.

As you can see, the dmesg command is a pretty nice interface in order to see kernel logs, but how is the dmesg command printing those results back to you?

In order to unveil the different mechanisms used, let’s see which processes and devices take care of Kernel logging.

Kernel Logging internals

As you probably heard it before, on Linux, everything is a file.

If everything is a file, it also means that devices are files.

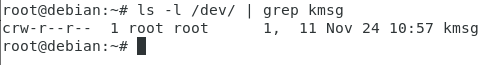

On Linux, the kernel ring buffer is materialized by a character device file in the /dev directory and it is named kmsg.

$ ls -l /dev/ | grep kmsg

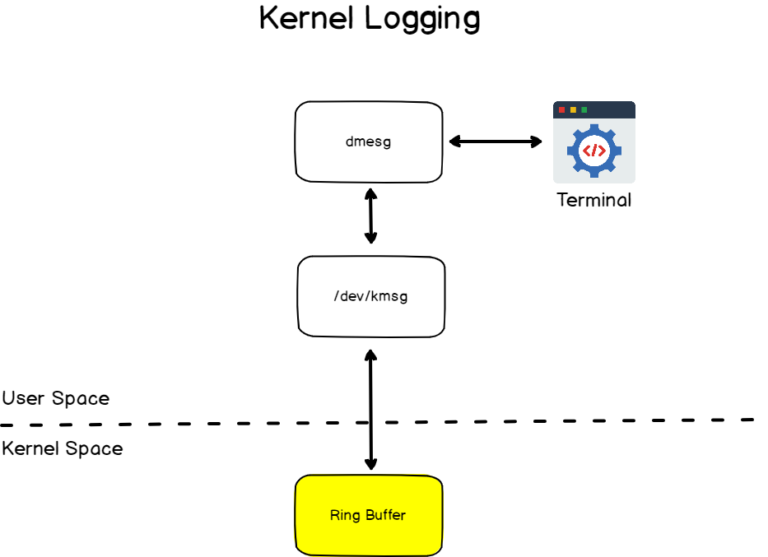

If we were to depict the relationship between the kmsg device and the kernel ring buffer, this is how we would represent it.

As you can see, the kmsg device is an abstraction used in order to read and write to the kernel ring buffer.

You can essentially see it as an entrypoint for user space processes in order to write to the kernel ring buffer.

However, the diagram shown above is incomplete as one special file is used by the kernel in order to dump the kernel log information to a file.

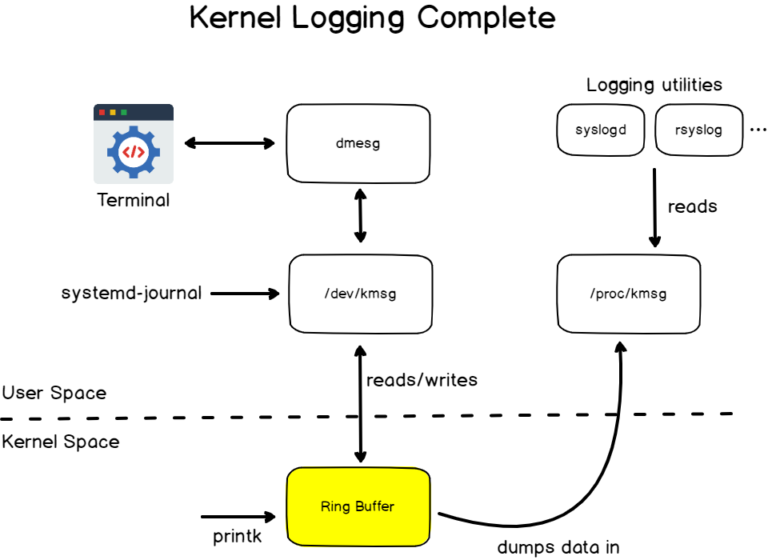

If we were to summarize it, we would essentially state that the kmsg virtual device acts as an entrypoint for the kernel ring buffer while the output of this process (the log lines) are printed to the /proc/kmsg file.

This file can be parsed by only one single process which is most of the time the logging utility used on the user space. On some distributions, it can be syslogd, but on more recent distributions it is integrated with rsyslog.

The rsyslog utility has a set of embedded modules that will redirect kernel logs to dedicated files on the file system.

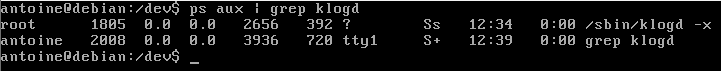

Historically, kernel logs were retrieved by the klogd daemon on previous systems but it has been replaced by rsyslog on most distributions.

On one hand, you have logging utilities reading from the ring buffer but you also have user space programs writing to the ring buffer : systemd (with the famous systemd-journal) on recent distributions for example.

Now that you know more about Kernel logging, let’s see how logging is done on the user space.

User side logging with Syslog

Logging on the userspace is quite different from logging on the kernel space.

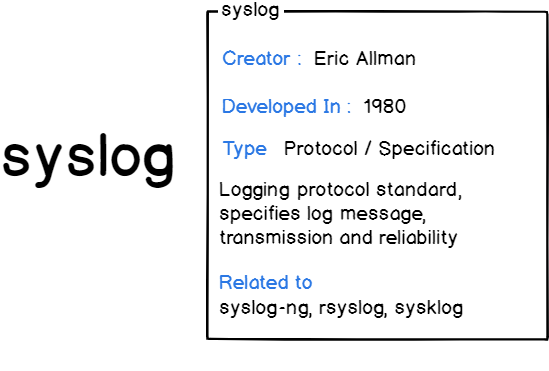

On the user side, logging is based on the Syslog protocol.

Syslog is used as a standard to produce, forward and collect logs produced on a Linux instance.

Syslog defines severity levels as well as facility levels helping users having a greater understanding of logs produced on their computers.

Logs can later on be analyzed and visualized on servers referred as Syslog servers.

In short, the Syslog protocol is a protocol used to define the log messages are formatted, sent and received on Unix systems.

Syslog is known for defining the syslog format that defines the format that needs to be used by applications in order to send logs.

This format is well-known for defining two important terms : facilities and priorities.

Syslog Facilities Explained

In short, a facility level is used to determine the program or part of the system that produced the logs.

On your Linux system, many different utilities and programs are sending logs. In order to determine which process sent the log in the first place, Syslog defines numbers, facility numbers, that are used by programs to send Syslog logs.

There are more than 23 different Syslog facilities that are described in the table below.

| Numerical Code | Keyword | Facility name |

| 0 | kern | Kernel messages |

| 1 | user | User-level messages |

| 2 | Mail system | |

| 3 | daemon | System Daemons |

| 4 | auth | Security messages |

| 5 | syslog | Syslogd messages |

| 6 | lpr | Line printer subsystem |

| 7 | news | Network news subsystem |

| 8 | uucp | UUCP subsystem |

| 9 | cron | Clock daemon |

| 10 | authpriv | Security messages |

| 11 | ftp | FTP daemon |

| 12 | ntp | NTP subsystem |

| 13 | security | Security log audit |

| 14 | console | Console log alerts |

| 15 | solaris-cron | Scheduling logs |

| 16-23 | local0 to local7 | Locally used facilities |

Most of those facilities are reserved to system processes (such as the mail server if you have one or the cron utility). Some of them (from the facility number 16 to 23) can be used by custom Syslog client or user programs to send logs.

Syslog Priorities Explained

Syslog severity levels are used to how severe a log event is and they range from debug, informational messages to emergency levels.

Similarly to Syslog facility levels, severity levels are divided into numerical categories ranging from 0 to 7, 0 being the most critical emergency level.

Again, here is a table for all the priority levels available with Syslog.

Here are the syslog severity levels described in a table:

| Value | Severity | Keyword |

| 0 | Emergency | emerg |

| 1 | Alert | alert |

| 2 | Critical | crit |

| 3 | Error | err |

| 4 | Warning | warning |

| 5 | Notice | notice |

| 6 | Informational | info |

| 7 | Debug | debug |

Syslog Architecture

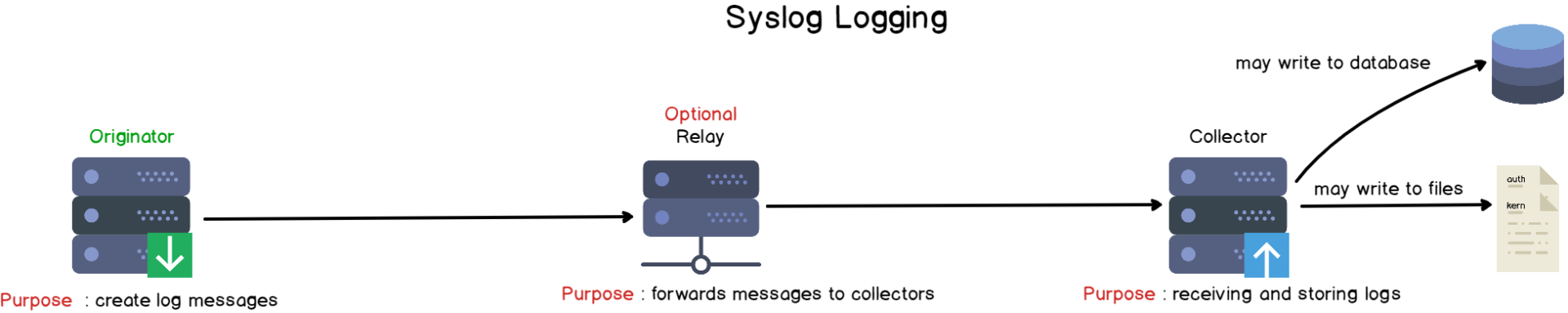

Syslog also defines a couple of technical terms that are used in order to build the architecture of logging systems :

- Originator : also known as a “Syslog client”, an originator is responsible for sending the Syslog formatted message over the network or to the correct application;

- Relay : a relay is used in order to forward messages over the network. A relay can transform the messages in order to enrich it for example (famous examples include Logstash or fluentd);

- Collector : also known as “Syslog servers”, collectors are used in order to store, visualize and retrieve logs from multiple applications. The collector can write logs to a wide variety of different outputs : local files, databases or caches.

As you can see, the Syslog protocol follows the client-server architecture we have seen in previous tutorials.

One Syslog client creates messages and sends it to optional local or distant relays that can be further transferred to Syslog servers.

Now that you know how the Syslog protocol is architectured, what about our own Linux system?

Is it following this architecture?

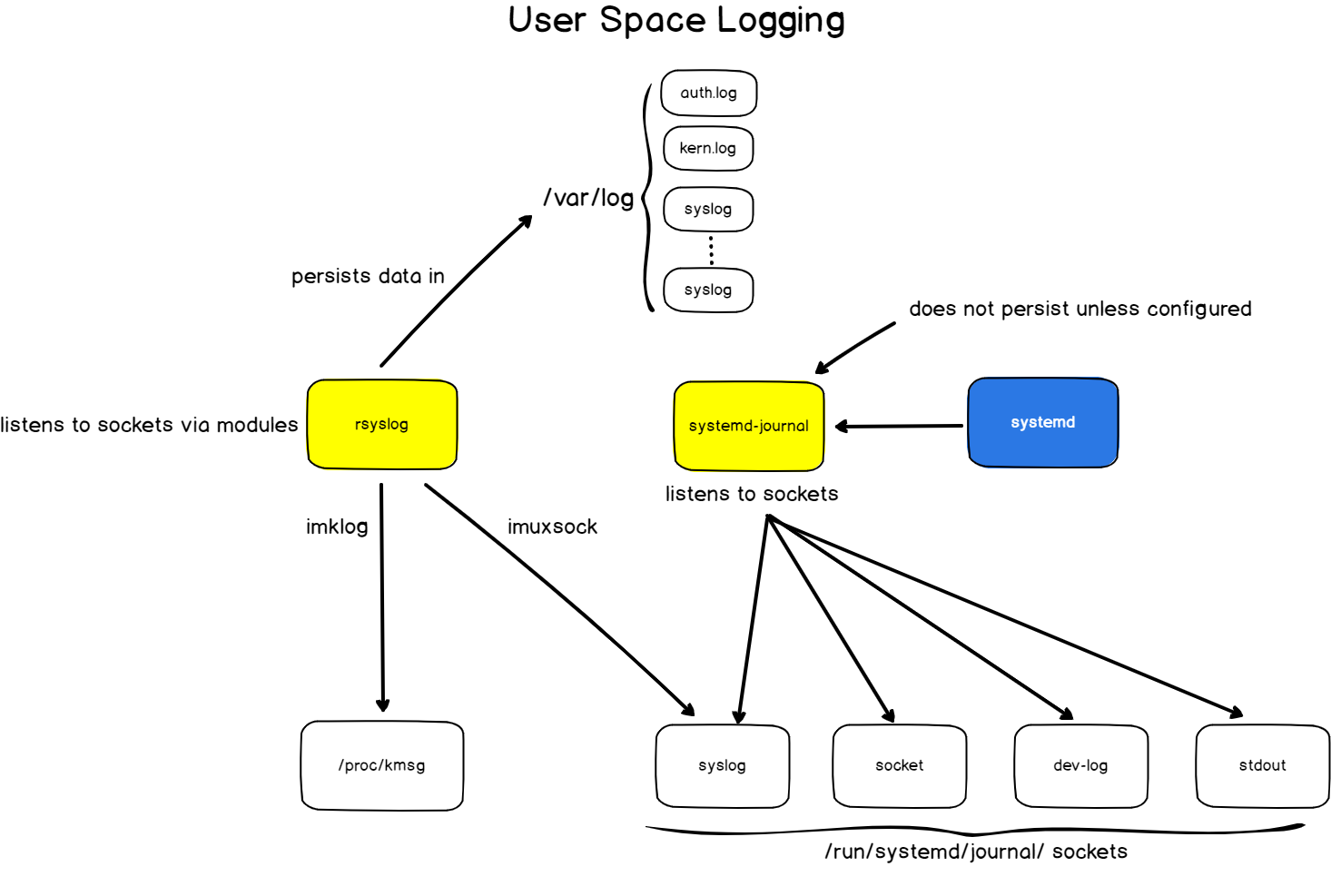

Linux Local Logging Architecture

Logging on a local Linux system follows the exact principles we have described before.

Without further ado, here is the way logging is architectured on a Linux system (on recent distributions)

Following the originator-relay-collector architecture described before, in the case of a local Linux system :

- Originators are client applications that may embed syslog or journald libraries in order to send logs;

- No relays are implemented by default locally;

- Collectors are rsyslog and the journald daemon listening on predefined sockets for incoming logs.

So where are logs stored after being received by the collectors?

Linux Log File Location

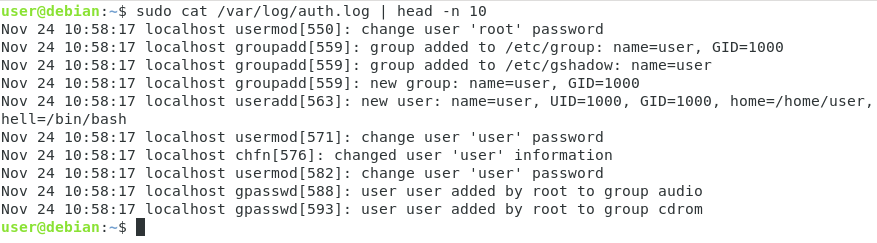

On your Linux system, logs are stored in the /var/log directory.

Logs in the /var/log directory are split into the Syslog facilities that we saw earlier followed by the log suffix : auth.log, daemon.log, kern.log or dpkg.log.

If you inspected the auth.log file, you would be presented with logs related to authentication and authorization on your Linux system.

Similarly, the cron.log file displays information related to the cron service on your system.

However, as you can see from the diagram above, there is a coexistence of two different logging systems on your Linux server : rsyslog and systemd-journal.

Rsyslog and systemd-journal coexistence

Historically, a daemon was responsible for gathering logs from your applications on Linux.

On many old distributions, this task was assigned to a daemon called syslogd but it was replaced in recent distributions by the rsyslog daemon.

When systemd replaced the existing init process on recent distributions, it came with its own way of retrieving and storing logs : systemd-journal.

Now, the two systems are coexisting but their coexistence was thought to be backwards compatible with the ways logs used to be architectured in the past.

The main difference between rsyslog and systemd-journal is that rsyslog will persist logs into the log files available at /var/log while journald will not persist data unless configured to do it.

Journal Log Files Location

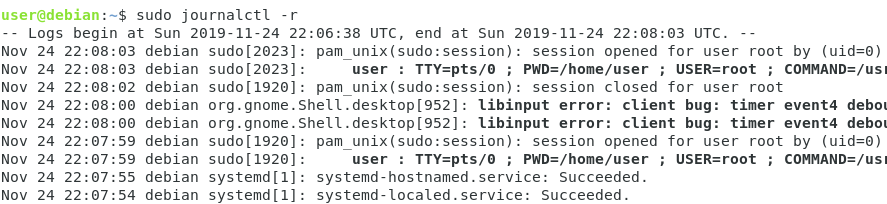

As you understood it from the last section, the systemd-journal utility also keeps track of logging activities on your system.

Some applications that are configured as services (an Apache HTTP Server for example) may talk directly to the systemd journal.

The systemd journal stores logs in a centralized way is the /run/log/journal directory.

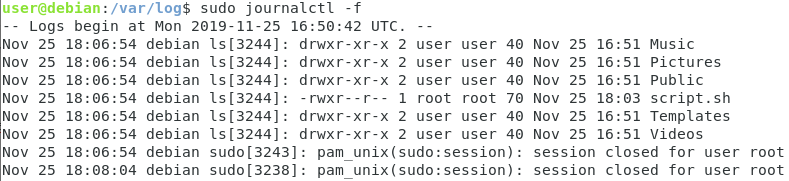

The log files are stored as binary files by systemd, so you won’t be able to inspect the files using the usual cat or less commands.

Instead, you want to use the “journalctl” command in order to inspect log files created by systemd-journal.

$ journalctl

There are many different options that you can use with journalctl, but most of the time you want to stick with the “-r” and “-u” option.

In order to see the latest journal entries, use “journalctl” with the “-r” option.

$ journalctl -r

If you want to see logs related to a specific service, use the “-u” option and specify the name of the service.

$ journalctl -u <service>

For example, in order to see logs related to the SSH service, you would run the following command

$ journalctl -u ssh

Now that you have seen how you can read configuration files, let’s see how you can easily configure your logging utilities.

Linux Logging Configuration

As you probably understood from the previous sections, Linux logging is based on two important components : rsyslog and systemd-journal.

Each one of those utilities has its own configuration file and we are going to see in the following chapters how they can be configured.

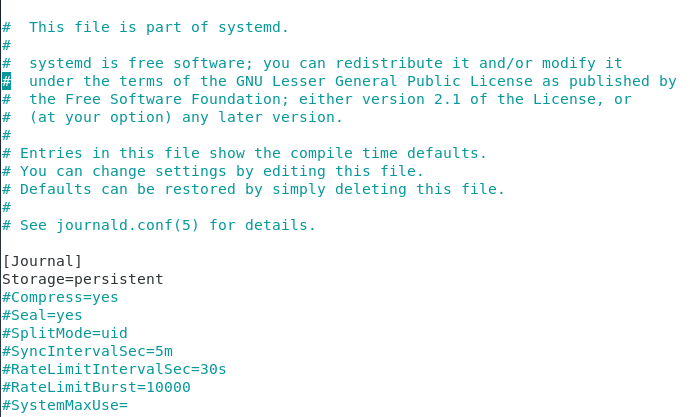

Systemd journal configuration

The configuration files for the systemd journal are located in the /etc/systemd directory.

$ sudo vi /etc/systemd/journald.conf

The file named “journald.conf” is used in order to configure the journal daemon on recent distributions.

One of the most important options in the journal configuration is the “Storage” parameter.

As specific before, the journal files are not persisted on your system and they will be lost on the next restart.

To make your journal logs persistent, make sure to modify this parameter to “persistent” and to restart your systemd journal daemon.

To restart the journal daemon, use the “systemctl” command with the “restart” option and specify the name of the service.

$ sudo systemctl restart systemd-journald

As a consequence, journal logs will be stored into the /var/log/journal directory next to the rsyslog log files.

$ ls -l /var/log/journal

If you are curious about the systemd-journal configuration, make sure to read the documentation provided by FreeDesktop.

Rsyslog configuration

On the other hand, the rsyslog service can be configured via the /etc/rsyslog.conf configuration file.

$ sudo vi /etc/rsyslog.conf

As specified before, rsyslog is essentially a Syslog collector but the main concept that you have to understand is that Rsyslog works with modules.

Its modular architecture provides plugins such as native ways to transfer logs to a file, a shell, a database or sockets.

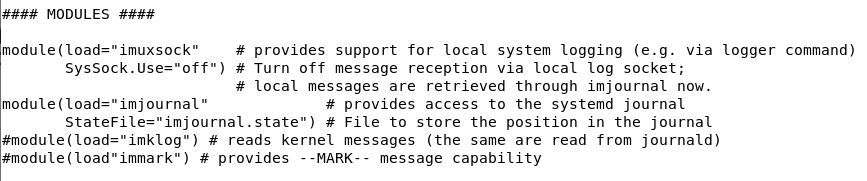

Working with rsyslog, there are two main sections that are worth your attention : modules and rules.

Rsyslog Modules

By default, two modules are enabled on your system : imuxsock (listening on the syslog socket) and imjournal (essentially forwarding journal logs to rsyslog).

Note : the imklog (responsible for gathering Kernel logs) might be also activated.

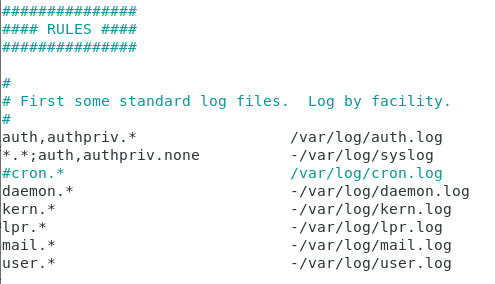

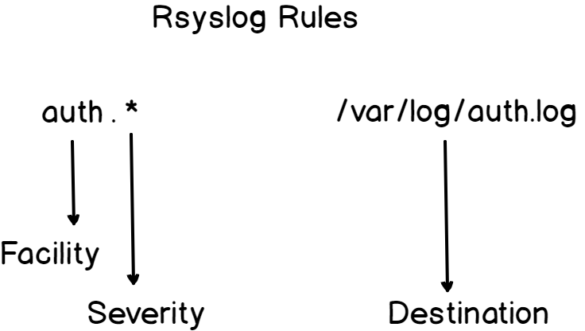

Rsyslog Rules

The rules section of rsyslog is probably the most important one.

On rsyslog, but you can find the same principles on old distributions with systemd, the rules section defines which log should be stored to your file system depending on their facility and priority.

As an example, let’s take the following rsyslog configuration file.

The first column describes the rules applied : on the left side of the dot, you define the facility and on the right side the severity.

A wildcard symbol “*” means that it is working for all severities.

As a consequence, if you want to tweak your logging configuration in order, say for example that for example you are interested in only specific severities, this is the file you would modify.

Linux Logs Monitoring Utilities

In the previous section, we have seen how you can easily configure your logging utilities, but what utilities can you use in order to read your Linux logs easily?

The easiest way to read and monitor your Linux logs is to use the tail command with the “-f” option for follow.

$ tail -f <file>

For example, in order to read the logs written in the auth.log file, you would run the following command.

$ tail -f /var/log/auth.log

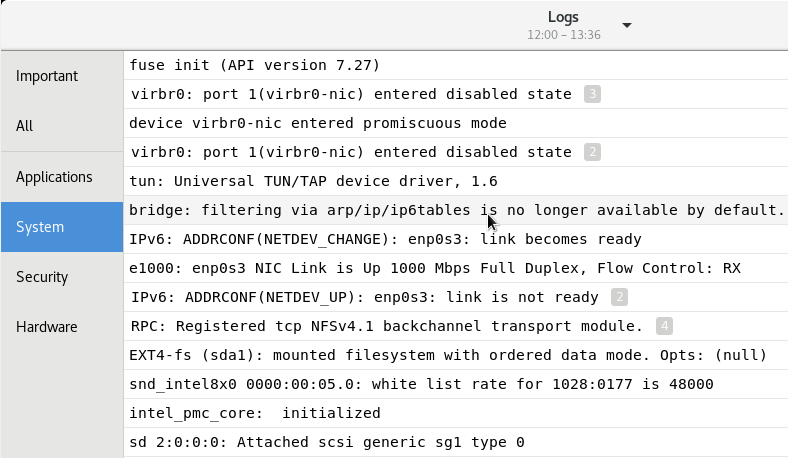

Another great way of reading Linux logs is to use graphical applications if you are running a Linux desktop environment.

The “Logs” application is a graphical application designed in order to list application and system logs that may be stored in various logs files (either in rsyslog or journald).

Linux Logging Utilities

Now that you have seen how logging can be configured on a Linux system, let’s see a couple of utilities that you can use in case you want to log messages.

Using logger

The logger utility is probably one of the simpliest log client to use.

Logger is used in order to send log messages to the system log and it can be executed using the following syntax.

$ logger <options> <message>

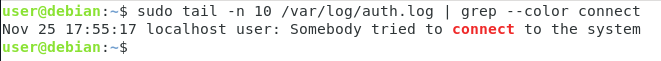

Let’s say for example that you want to send an emergency message from the auth facility to your rsyslog utility, you would run the following command.

$ logger -p auth.emerg "Somebody tried to connect to the system"

Now if you were to inspect the /var/log/auth.log file, you would be able to find the message you just logged to the rsyslog server.

$ tail -n 10 /var/log/auth.log | grep --color connect>

The logger is very useful when used in Bash scripts for example.

But what if you wanted to log files using the systemd-journal?

Using systemd-cat

In order to send messages to the systemd journal, you have to use the “systemd-cat” command and specify the command that you want to run.

$ systemd-cat <command> <arguments>

If you want to send the output of the “ls -l” command to the journal, you would write the following command

$ systemd-cat ls -l

It is also possible to send “plain text” logs to the journal by piping the echo command to the systemd-cat utility.

$ echo "This is a message to journald" | systemd-cat

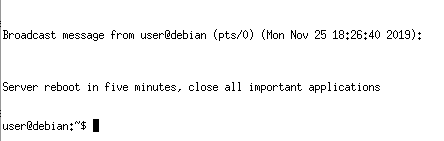

Using wall

The wall command is not related directly to logging utilities but it can be quite useful for Linux system administration.

The wall command is used in order to send messages to all logged-in users.

$ wall -n <message>

If you were for example to write a message to all logged-in users to notify them about the next server reboot, you would run the following command.

$ wall -n "Server reboot in five minutes, close all important applications"

Conclusion

In this tutorial, you learnt more about Linux logging : how it is architectured and how different logging components (namely rsyslog and journald) interact together.

You learnt more about the Syslog protocol and how collectors can be configured in order to log specific events on your system.

Linux logging is a wide topic and there are many more topics for you to explore on the subject.

Did you know that you can build centralized logging systems in order to monitor logs on multiple machines?

If you are interested about centralized logging, make sure to read our guide!

Also, if you are passionate about Linux system administration, we have a complete section dedicated to it on the website, so make sure to check it out!